by Andrew Tracy

Reverse Shot

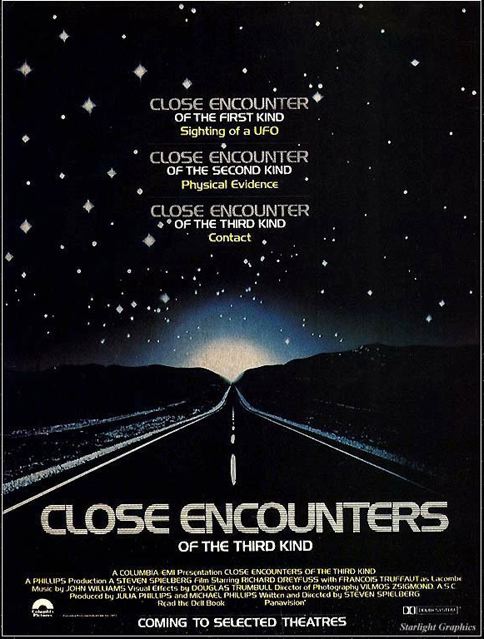

What more can one say about Jaws? There are only a handful of other American films—The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, Casablanca, Citizen Kane, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, Apocalypse Now—whose making and reception have been as extensively documented, the history of their respectively fraught productions only further hallowing their legendary status. And like those films, Jaws has taken on the stature of myth—but a myth of what? Oz, GWTW, and Star Wars are escapes into fantastic other worlds and/or the otherworldly past, Casablanca a fantasy of an otherworldly present; Kane, 2001, and Apocalypse synonymous with the Olympian ambition (and/or hubris) of their makers. Jaws’ brand of escapism is far less comforting than the respective fantasy lands of the first batch, and while it hews far closer to that latter wunderkind narrative—clever, untried kid helms disastrous production, improvises day by day, emerges with masterpiece—it is less intrinsically tied to the person of its director than are the Welles, Kubrick, and Coppola films to their respective creators. Apart from the rare direct avatar (Close Encounters of the Third Kind’s Roy Neary, E.T. ’s Elliott), there is no equivalent in Steven Spielberg’s films to such refractive autoportraits/critiques as Welles’s Charles Foster Kane/Hank Quinlan/Falstaff or Coppola’s Michael Corleone/Kurtz/Tucker.

Far less of a self-styled intellectual than Welles, Kubrick, or Coppola—and certainly far less of a masterful personality—Spielberg is accordingly a more diffuse, though no less unmistakable, presence in his own work. This nowhere-man quality is all the more remarkable in that Spielberg, with Kubrick but unlike Welles or Coppola, has achieved the Benjaminian feat of founding his own genre—a genre of which he is the only true practitioner (see J. J. Abrams’s failed Spielbergian pastiche Super 8). Unlike such former associates as Joe Dante or Robert Zemeckis, who merrily pillage the rag-and-bone shop of pop culture, Spielberg does not so much refer to the cinematic past as imbibe it. Even though he has worked in almost the full range of available genres, Spielberg’s key films are enveloping, holistic, self-sustaining in a manner that belies their generic roots. Jaws’ provenance can be traced to the mainstreaming of the horror film begun by Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist, and the death-as-spectacle decadence of the disaster film cycle, but it is fundamentally unclassifiable as anything but itself; Close Encounters and E.T. belong to the history of the science-fiction film, but they do not so much work within the genre as use its lineaments to create, as Stanley Kauffmann put it, “event[s] in the history of faith”; the Indiana Jones outings are certainly “adventure films,” but their manic intensity transports them to an entirely different plane; Saving Private Ryan is not so much a war film as (in intention at least) the war film.

The extremity, and inimitability, of Spielberg’s aesthetic stands in inverse proportion to the modesty of his intellectual resources, at least when stacked against his comparable director-demiurges. Welles, Kubrick, and Coppola freighted (and sometimes sunk) their films with a wealth of artistic, literary, historical, political, and philosophical reference points; Spielberg, as surely even his most ardent supporters would agree, has nothing comparable to such extra-cinematic erudition. Not, of course, that he needs it. Spielberg’s profundity—and even this perennial skeptic admits that the man has had his moments of it—is of an intuitive, affective variety that at its height is positively oceanic. “If Spielberg is what’s called a post-literate, he has the strengths as well as the defects of post-literacy,” wrote Stanley Kauffmann in his brilliant review of Close Encounters. “The long, last, thrilling scene overpowers us because, given any reasonable chance to be overpowered by it, we want to be overpowered by it. . . . That finale doesn’t bring us salvation, it brings us companionship. We are not alone. That belief seems potent in itself, and the film makes the belief believable. The way to faith seems to be through the transubstantiation of the twelve-track Panavision film.”

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment