by Dan Akira Nishimura

Bright Lights Film Journal

When Alfred Hitchcock wrapped Psycho (1960), it was years before the sequel became commonplace. No one expected Ben Hur (1959) or Spartacus (1960) to continue on with new adventures. "The End" meant just that, for the story and the characters. So it may have come as a surprise to Anthony Perkins when his Norman Bates character was revived thirteen years later in Psycho II (1983). In some ways, however, he had never stopped playing him.

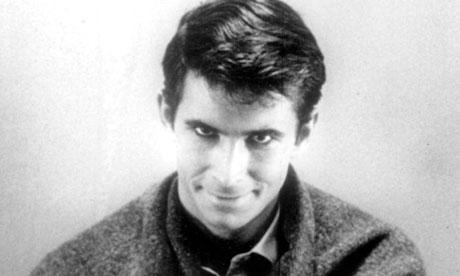

A dreamy-eyed staple of fan magazines of the late 1950s and early '60s, Perkins was cast against type as the psychotic killer. Because of the enormous success of Psycho, he immediately became identified with the role. Although he at first resisted, Perkins returned to Norman Bates again and again, in one form or other. Norman's twitchy eccentricity seeped into many of Perkins' post-Psycho performances that preceded the run of sequels. His paranoid bank manager Joseph K. in The Trial (1962), the preppy-with-a-secret Dennis Pitt in Pretty Poison (1968), and the amnesiac sculptor Charles Van Horn in Ten Days Wonder (1971) all bear the mark of Norman Bates. In this essay, we'll look at how Perkins became indistinguishable from Norman and why he was never "finished" with him. Perkins set the stage for the emergence of the creepy but sympathetic pretty-boy psychopath next door. Without Psycho, sweet-faced Tony Curtis may have had a difficult time convincing producers he could play Albert DeSalvo in The Boston Strangler (1968). Another real-life Norman, serial killer Ted Bundy, was celebrated in books and a television miniseries. Anthony Perkins was born in 1932, the year Adolf Hitler seized power. Perkins was the son of the actor James Ripley Osgood Perkins, who died onstage when Tony was five. Growing up in the shadow of the Second World War and surviving the death of a parent must certainly have affected him. In any case, there's an unease built into his screen personae whether he's playing high-strung baseball player Jimmy Piersall in Fear Strikes Out (1957) or Norman Bates.

"Psycho begins with the normal," writes Robin Wood, "and draws us steadily deeper and deeper into the abnormal; it opens by making us aware of time, and ends with a situation in which time has ceased to exist."1 It's difficult to imagine the world before Psycho and its countless imitators. Known as the eccentric director of big-budget, wide-screen Technicolor spectacles, Hitchcock planned to make Psycho for $800,000, even then not a large sum for a major motion picture. It was shot by John L. Russell with a get-it-done-quick sensibility learned from television. From the success of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Hitchcock sensed that movie audiences were ready for a good scare. The slashing violins of Bernard Herrmann's soundtrack were vital to creating tension in the viewer. Although cinematic innovations were few, the film was notable as a triumph of marketing and for elevating Anthony Perkins to screen immortality. It also marked a shift in attitudes about sex as the 1960s began. David Thomson writes:

The subversive secret was out — truly this medium was prepared for an outrage in which sex and violence were no longer games but were in fact everything. Psycho was so blatant that audiences had to laugh at it, to avoid the giddy swoon of evil and ordeal. That title warned that the central character was a bit of a nut, but the deeper lesson was that the audience in its self-inflicted experiment with danger might be crazy, too. Sex and violence were ready to break out, and censorship crumpled like an old lady's parasol. The orgy had arrived.2

No matter the subject matter, Hitchcock stressed the idea of "pure film" where the pictures tell the story. Perkins, with his expressive face and physical style of acting, is well suited to a Hitchcock movie. As Norman, he's full of nervous tics one moment and longing gazes toward his female co-stars the next. As such, he's the perfect foil for Hitchcock, who was known to be uncomfortable with women. Writes Robin Wood: "Hitchcock isn't interested in acting, certain actors, left to their own devices, are able to seize their chances and create their own performances independently; there is more reason to deduce that there are certain performances — or more exactly, certain roles — which arouse in Hitchcock a particular creative interest."3

As a child, Hitchcock was required to stand at the foot of his mother Emma's bed and report on his perceived transgressions, something that continued into adolescence. In Joseph Stefano's screenplay of Psycho, the mother of Norman, or at least the part of her that survives in his head, is all-powerful. "A boy's best friend is his mother," he says. Perkins plays the dual role of Norman and the deceased Mrs. Bates. The homicidal maniac as cross-dresser is another aspect of Psycho that wasn't "finished." Twenty years later, Michael Caine would put on the wig in Brian De Palma's Dressed to Kill (1980).

In the Franz Kafka source novel for the Orson Welles film The Trial, Joseph K. is an innocent man wrongly accused. Perkins plays him as a tightly coiled nervous wreck who's oddly attractive to women. His interpretation makes it appear that Joseph must be guilty of "something." Presumably to escape typecasting as Norman, Perkins fled to Europe, where Welles had also taken refuge during the years of the Hollywood blacklist.4 In The Trial (1962), Welles had creative control, and stylistically it was one of the best of his European films.5 An irrational universe with its rows of desks manned by overworked clerks is depicted in stunning black-and-white by Edmond Richard's camera. Location shooting, including what was then the Gare dOrsay train station, only adds to the surreal quality. Reflected light, something that Welles perfected with Gregg Toland shooting Citizen Kane (1941), is used extensively. At the center is Perkins as Joseph K., a man put through a trial (Le proces in French) not limited to a courtroom. Just as Norman is shocked by what he considers the outrageous accusations made against him, Joseph feels put upon and harassed by an incomprehensible bureaucracy. There are some differences, though. With Norman, the Mother is a constant presence watching his every move, whereas Joseph lives in fear of the Father as represented by the State. Welles is The Advocate, who seems more like an adversary. As portrayed by some of the most popular European actresses of the time including Jeanne Moreau and Romy Schneider, women are drawn to Joseph as to an abandoned infant. He appears to be able to consummate some of these encounters, yet he remains unsatisfied.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment