by Roger Leatherwood

Bright Lights Film Journal

1. WHO CARES ABOUT NOSTALGIA ANYMORE?

Personal Archives in the Absence of a Corporate One

Prior to about 1980, Hollywood seemed perversely uninterested in its own history, inadvertently or intentionally neglecting its production materials (not to mention old film elements) that often were left rotting behind studio vault walls and taking up valuable real estate and given away or maybe dumped in the bay some foggy night. Since the advent of home video and the ever-increasing value of catalog titles, new digital (expensive to license, cheap to deliver) formats and the promise of the long tail, studios have increasingly strived to make their films and TV shows available to as wide an audience as possible for as long as possible, including offering merchandise that depicts the characters, graphics, and designs on any and all appropriate items from toys to smartphone cases. This constant upkeep of the presence of the brand of a filmed property in the culture keeps it in the public's memory, perhaps motivating sequels, spin-offs, and other ancillary revenue. And all this has to be archived and kept careful track of.

In some rare instances, producers have maintained archives, private or set up as museum spaces to display props, costumes, and other ephemera.1 But examples of industrial archival curation are sparse, and while the films themselves may enjoy an afterlife in repertory houses or at museum screenings, physical archives are seldom open and, unless they involve Stanley Kubrick or some other storied career, don't go on the road.2

Legacy production materials of motion pictures from draft scripts to set designs to production stills not intended for the public eye often end up forgotten, if they aren't purloined from under the noses of archivists who never notice them missing. The majority of productions dating from before the 1980s suffer from almost nonexistent archival profiles, and have no cultural presence. As a result they remain invisible to cultural memory. In the absence of digital or other marketing engagements now common to recent cross-platform franchise properties, marketing ephemera surrounding the releases ("collateral" to use the marketing term) gets fetishized as the proxy for favorite films, and authentic original posters for such films as King Kong (1933) to Star Wars (1977) go for thousands of dollars on auction sites,3 signifiers of the original and authentic industrial marketing impulse and of the cultural moment in which these were the only legitimate proxy outside of actual viewership.

Ari Kahan's website devoted to Phantom of the Paradise (1974), The Swan Archives (www.swanarchives.org),4 has curated a collection of marketing materials that reanimates the era of this forgotten film's release. Launched in 2006 with the results of 30 years of collecting posters, stills, and other materials, the site functions not only as a resource for the film's fan community but also as its only surviving archive that creates and even defines a new audience for the film. Made up of over 400 pictures of objects, screengrabs, and detailed narratives of the film's genesis, production, marketing, and editing variants adding up to over 75,000 words, as explications of the film's themes, subtexts, and historical context it presents a comprehensive, exhaustive, and passionately rendered archive of the history and reception of the film and a film of its type in the mid-'70s cultural landscape, all in the absence of any attempts by the corporate rightsholders to do so.

2. RECORDING LIVE FOR THE SWAN ARCHIVES

Objects, Their Meanings, and the Importance of Timing

Working online, within view but beyond the traditional reach of normal gatekeepers of intellectual property, Kahan illustrates a new mode of archival behavior and engagement possible in digital environments that revivifies obsolete (in this case, intellectual) property and curates and recontextualizes it. At the same time, Kahan's efforts reflect a rather conservative and closed approach to how an archive is built and functions, in large part by taking pains to protect the assets from promiscuous sharing as well as the context in which they're viewed. By dint of his existence in a landscape that is relatively unexplored, Kahan engages the tension between how audiences and corporate rightsholders control, negotiate, and create new meanings surrounding their properties. His site allows audiences to engage with artifacts outside traditional archival walls; investigates how archival activity affects digital, personal, and other casual engagements with film texts; and points the way in which such sites create new narratives around the texts themselves.

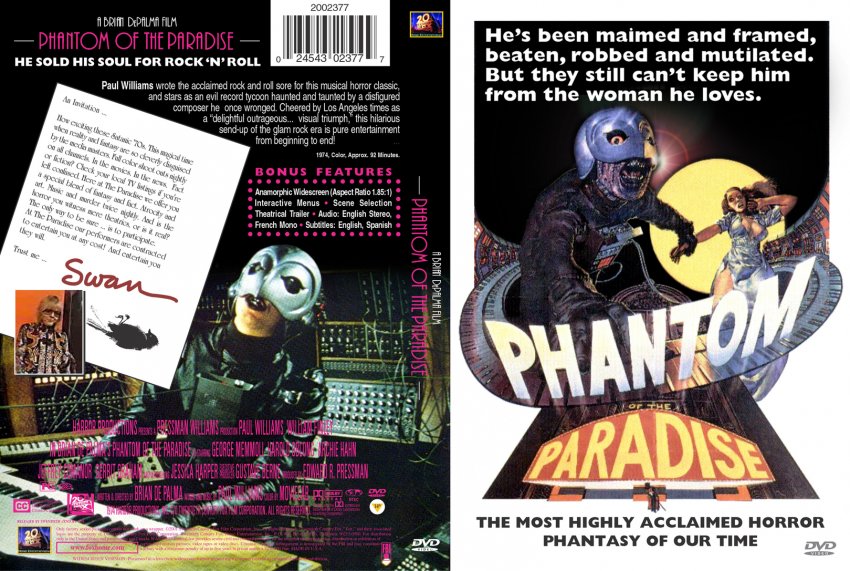

Phantom of the Paradise, written and directed by Brian De Palma and starring Paul Williams, William Finley, and Jessica Harper, was released by 20th Century-Fox in 1974. Appearing amid the rich cultural tapestry that also included The Godfather Part II, Chinatown, The Towering Inferno, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, it was largely unsuccessful in finding a wide audience and was relegated to relative obscurity on the second half of double bills before being remarketed to secondary markets with a revamped ad campaign six months later.

A quirky, stylized, and fleet-footed if unwieldy blend of horror and fantasy taking place in a rock-and-roll setting, Phantom of the Paradise attracted the attention of horror film and science fiction fans rather than a teenage rock music audience. Its plot borrows predominantly from the 1943 and 1962 film versions of Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera5 as well as the German legend of Faust (the music mogul Swan played by Williams sells his soul for success). By virtue of its pop sensibilities, its fanciful critique of corporate greed, and its stylized filmmaking techniques (a harbinger of the Grand Guignol style Brian De Palma would develop to greater effect in Carrie [1976] and Scarface [1983]), the film slowly built a cult following. As a meta-narrative about popular music as well as a satire of celebrity culture that parodies the very elements that audiences might enjoy about it (flashy rock production numbers, fan worship), the film likely alienated the audiences it expected to attract, until a revised ad campaign repositioned the film as a horror/thriller as opposed to a musical (the Style C poster tagline is "He's been maimed and framed, beaten, robbed, and mutilated. But they still can't keep him from the woman he loves"). Moderately more successful, it attracted enough attention to be written up in various science fiction and film magazines.

To Read the Rest

No comments:

Post a Comment