by John Engle

Bright Lights Film Journal

...

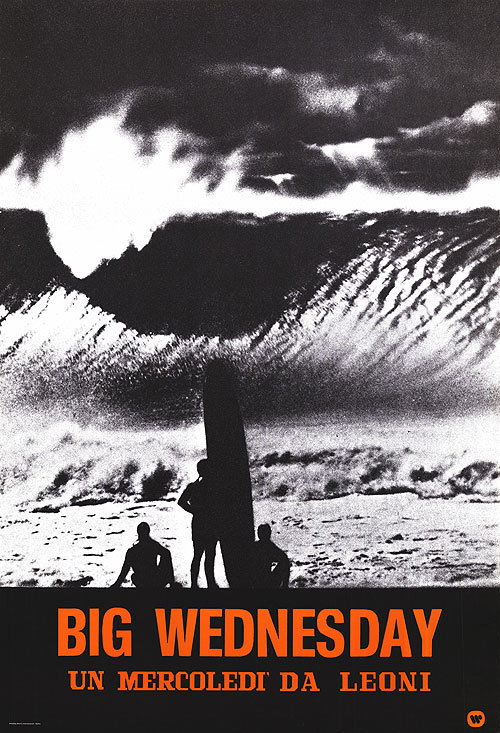

The tensions of these real and screen lives have in large part remained those of the film genre Gidget engendered. In the half-century since, from the Beach Party franchise and its early '60s spin-offs, through Big Wednesday, Point Break, Blue Crush, and many others, and on to Chasing Mavericks in 2012, filmmakers have gone to the sand a couple dozen times to produce narratives either focused expressively on surfing as sport or obsessive life choice, or at least as significant background informing and directing the film's meaning. The result has been movies that are often more incisively pertinent in their treatment of growing up, family tensions, a world of dizzying social change, race and class, and the seductive lure of commerce and appearance than their wicked barrels, great tans, and dudespeak might presage. With an eye to the meanings behind their attractive surfaces, I'll be looking at a handful of these, at least one from each decade, for the most part relatively high-profile examples of a film type that, if rarely the source of smash hits, has generally met with commercial success. Hardening firmly in place by the 1970s, a highly restrictive formula thereafter rules the near totality of these films: given their interest in young people on the cusp of adult life, it's not without a certain logic that they return repeatedly to such story elements as the wise mentor, the temptation to sell out, the preparation sequence, and the concluding challenge or competition. The remarks to follow will examine the genre's creation in the beach-craze '60s, then turn to its elaboration in what one might consider the main line of "classic" surf films, with their reliably formulaic focus on childhood's end; the conclusion will explore how, while remaining generally faithful to established patterns, certain films have brought within their widened purview broader social and political issues. With the exception of Bruce Brown's The Endless Summer (1966) — a documentary but vaguely story-centered and, in any case, so iconic as to be compulsory — all of the films under discussion are pure narratives. As such, they should be distinguished from the grainy collections of hot rides Greg Noll brought to stoked kids in countless multipurpose halls and their often lyrical or thrilling cinematic descendants. Whether big deals like Riding Giants and Step into Liquid, or smaller, edgier efforts like BS!, these documentaries are absolutely central to the surfing subculture and merit separate study, with their specialist target audience, their shared values, and visual assumptions.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, the first treatments of waveriding were documentary in nature and aimed at the widest possible audience. Like les Pathé-Frères, who put together 100 minutes on Le Surfing: Sport national des iles Hawaii in 1911, filmmakers in the first half of the century responded periodically to a curious public's hunger for images of exotic locales and practices that, even in the era of grand liners and early aviation, remained largely inaccessible. By the thirties, in any case, the word on surfing was getting out, if Hawaiian Holiday, the first cinematic narrative treatment of the sport, is any indication. In this 1937 Mickey Mouse featurette, Goofy recklessly challenges waves that, with the typical extraordinary range of Disney's animation teams, manage at once to be dumb funny, anthropomorphically nasty, and possessed of a frothy, sculpted loveliness drawn straight from Hokusai. While the cartoon is (somewhat speciously) considered the source of the term goofy-footed for surfers who, like its hero, lead with their right foot, its variation on the timeless theme of the arrogant individual chastised by a recalcitrant natural world in fact says little more about surfing than that it was just edging into the public consciousness. It would take the '50s and early '60s and the sport's headlong drop into popular culture before filmmakers would begin to recognize and exploit its rich visual and thematic possibilities.

And what visuals, for there is something basically unbelievable about human beings standing up on a tumbling wave, not to mention carving sleek sweeps and tight reverses back up its face. Cinematically, what's not to like about good-looking kids in a dream locale practicing a potentially dangerous sport that, even straight-on from a fixed shore location in black and white, films like a million bucks? Considered a moment, however, the scene is much more than its very pretty pictures, in large part because of the richly conflicting signals it emits. As sport, identity definer, and style locus, the surfing we have come to know these last decades is a space of, variously, big-money competition, reverent communication with the natural world, heavy partying, one-to-one confrontation with appalling physical force, proprietary localism of the ugliest sort, New Age self-discovery. It is a counterculture and a culture, a way to rebel and a way to grow up, and some live an entire adult life, work and all, still somehow rhythmed by the daily wave report. Surfing is the Beach Boys sweet in their striped Kingston Trio short-sleeve button-downs, and it's Dora dive-bombing kooks and bouncing checks. It's the garden and the salesmen who slither into it. Let's go surfin' now, everybody's learnin' how, we are joyfully urged, but to paddle out as the new guy is in fact to try entering the most closed of societies. Surfing can seem like an ocean of style, posing, and attitude, but out in the impact zone and beyond, the superficial abruptly washes off. To choose a short board or long, three fins or one, can be no less than to define different selves and value systems.

The very physical space offers an equally rich palette of thematic opportunity. From knee-high kids' stuff to Fukushima, pure fluid energy rears in defiance at sudden, solid resistance. The arriving swell is pattern and endless variety, or as Laird Hamilton says of the big ones in The Wave, "it's never the same mountain" (72). Proceeding in stately sequence, breakers seem all ruler-edged order, but of course they are also sites of chaos and fear. There the simple can become "in practice immediately complex," writes Woolf in To the Lighthouse, "as the waves shape themselves symmetrically from the cliff top, but to the swimmer among them are divided by steep gulfs, and foaming crests." Wild swings of perspective rule the sand as well, for what place is more one for sun-drenched, thought-free lotus-eating than the beach. Yet on that thin strip of dry land the tragic drama of our collective addiction to fossil fuels will play out first. And even carefree Waikiki lies hard by an ocean's unfathomable mass with its troubling, timeless reach of myth and suggestion. It is on the shore after all that Wordsworth rejects that world that is too much with us, yearning seaward to affirm the deeper truths of Proteus and Triton. The beach is just the beach, and it is much more than that. The greatest of the wavewriters, Daniel Duane, recognizes the way the surf scene can encode paradox, locate that sweet spot where the deeply complex and the unreflective simple both somehow find their footing.

...

To Read the Entire Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment