by Christina Marie Newland

Bright Lights Film Journal

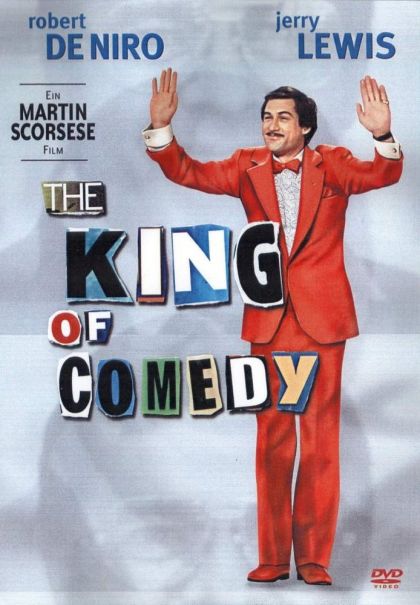

Robert De Niro as delusional acolyte to the stars, Rupert Pupkin, and Jerry Lewis as a mirror-image of his own talk-show comedian persona, Jerry Langford. Sandra Bernhard plays a supporting role as another hyperactive super-fan, Masha. The King of Comedy, written by Paul D. Zimmerman, does not resemble a typical Scorsese picture; the camera is pinned in place instead of roving around. This is seemingly to facilitate our unflinching stare into the lives and behaviour of the characters, when often we want nothing more than to look away. Scorsese's films usually teem with passion and activity, but Pupkin's world is more sedate, colder. Scorsese's go-to director of photography, Michael Chapman, turned down work on the film because of the director's choice of style: "His plan was to use largely empty sets, flat lighting, and old-fashioned box-like framing" (Rausch 102). Essentially, it was filmed to look like television.

Scorsese once again deals with an obsessional pursuit, a common theme in his work. Rupert Pupkin's obsession is particularly emblematic of the twenty-first century; it extends beyond the traditional pursuits of money and power, pursuing instead something more fleeting and all too modern: fame. More specifically, fame for fame's sake: fame predicated not on riches nor on talent but merely on the desire to be seen and idolized. This desire is what consumes De Niro's Rupert, a twitchy, perennially polite wannabe comedian who refuses to take no for answer when he meets his idol, Jerry Langford. He misunderstands Langford and his entourage's continual brush-offs, revealing his desire not merely to be around Jerry but to emulate him and eventually usurp him. He begs Langford for a guest spot on his hit television show, fantasises about Langford deferring to his ego, and eventually becomes deluded enough to appear uninvited at the celebrity's country house, only to be humiliatingly turned away in front of his crush, Rita (Diahnne Abbott). He and Masha then decide to take matters into their own hands and kidnap Jerry with a toy gun, demanding a spot on the show in exchange for Jerry's safety. Rupert is then allowed to perform his comedy routine on television. With startling irony, Rupert's bid for fame works, and although he is sentenced to prison for kidnapping, he is given a short sentence and comes out of prison famous, writing a best-selling book and receiving his own television show. The ironic conclusion to the film emphasizes its satirical look at the American obsession with empty fame, owing some debt to the 1976 Sidney Lumet film, Network.

The rise of consumerism and tabloid celebrity culture in the late 1970s and '80s is dealt with in both Network and The King of Comedy, but they become uncannily more accurate as time has passed, predicting the rise of reality television, social networking, and the disposable celebrity. Rupert simply decides, in the same aggressive manner as his Scorsesean compatriots, that his 15 minutes will be gained at any and all costs. The overnight celebrity becomes the new fixation of the American dream. The King of Comedy was poorly received, both by audiences and critics. "Unlike the context for Scorsese's earlier films, by the time of The King of Comedy, there was no longer an American film culture that encouraged or even allowed for challenging work" (Raymond 30). Considering the context of 1980s Hollywood and its "Reaganite entertainment" — escapist, often anti-intellectual blockbusters that provided happy endings and visceral enjoyment, it is easy to understand why the vulnerability and discomfort in The King of Comedy missed the mark with audiences. The overall cost of the film was recorded at $20 million; its domestic gross was roughly $2.5 million. It didn't do the film any favors that it was marketed as an outright comedy; it certainly is not that, though it has many darkly comic moments. Critics were more generous than audiences, but also offered some intriguing clues as to why the film flopped. Roger Ebert, for example (typically a Scorsese enthusiast), called the movie, "unsatisfying," "frustrating," and an "emotional desert," though he goes on to say that it is not by any means a "bad movie." Pauline Kael called it precisely that, going on to say that it gave her "cold creeps" and that it was "empty" (458). It is interesting that there seems to be a level of discomfort with both critics about the feelings the film evokes; both rightly refer to its unexpected coldness and the emotional distance of its characters, but another aspect also seems at play, one that William Ian Miller suggests: "the unfunny comedian humiliates himself and one of the sure indications that you are watching someone humiliate himself is that you will be embarrassed by the display" (329).

To Read the Rest

No comments:

Post a Comment