by Joshua Land

Moving Image Source

What makes a film a successful literary adaptation? Ask a random literate moviegoer, and they're likely to answer that a good film adaptation should be "like the book" (or play). In other words, a successful adaptation is a faithful adaptation. What then is a faithful adaptation? One that follows the story of the original text, of course. It's this fixation on story that prompts the common contention that most great modernist and postmodernist novels, which often either lack a traditional story or integrate story elements with discursive material, are "unfilmable." One possible strategy of adaptation is to "flatten out" the original by simply discarding everything that doesn't move the story along, as in Philip Kaufman and Jean-Claude Carrière's version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, a conventional 1980s Euro-prestige picture that preserves the novel's plot line while eliding the philosophical digressions and ruminations on love and kitsch that are essential to its meaning. So is it a successful adaptation of Milan Kundera's novel? Well, that depends on what you mean by "successful."

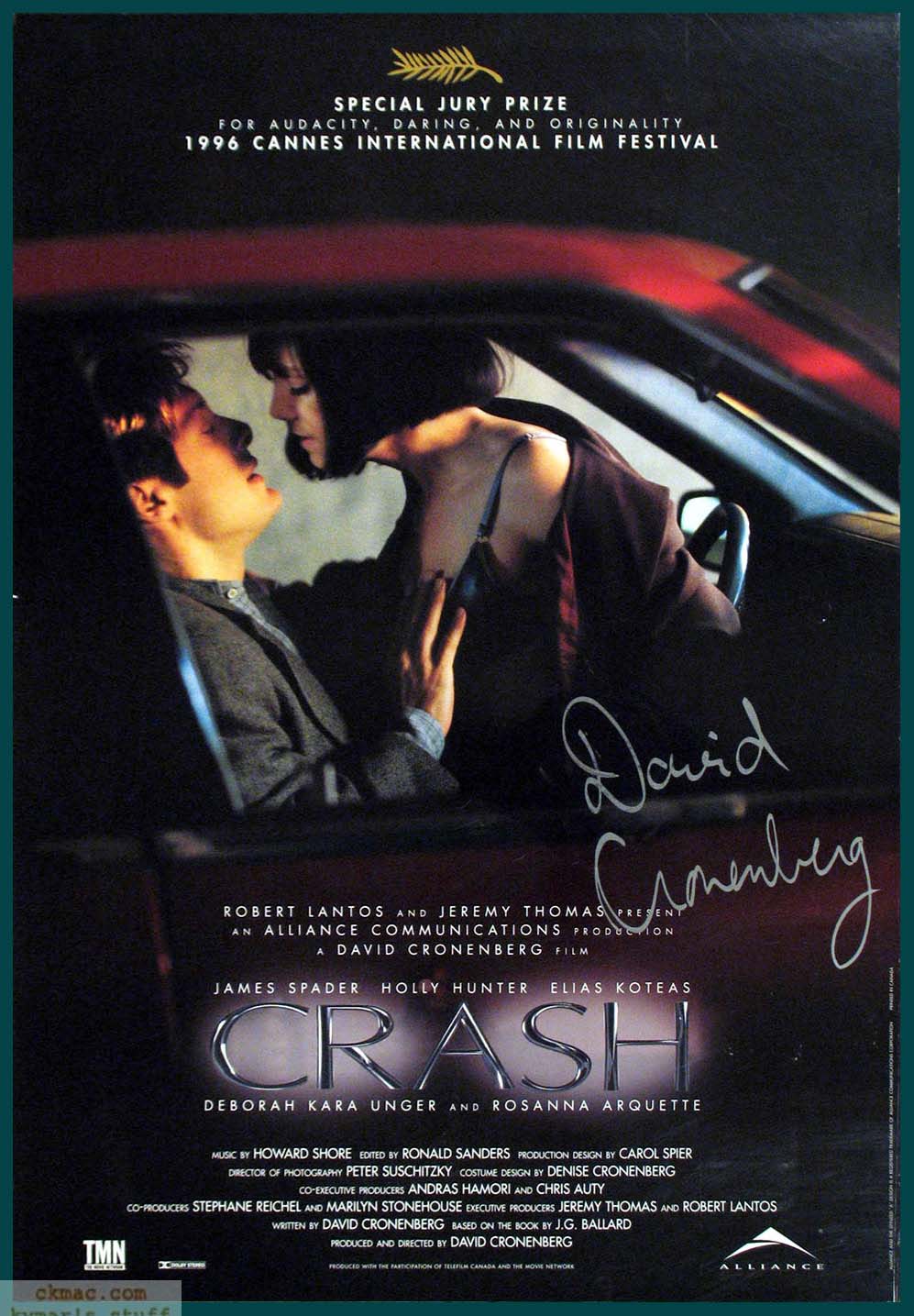

Over the latter half of his career, David Cronenberg has intervened in this tiresome discussion with a series of what have been termed "impossible adaptations." In films like Naked Lunch (1991) and Crash (1996), adaptations of novels once regarded as unfilmable, Cronenberg approaches the problem of adaptation from a different angle. One of these films closely follows the story of its source novel and one does not, but both could be described as successful—and even, after a fashion, faithful—adaptations.

Discussion of adaptations is often haunted by the unresolved question of whether a film should be regarded as merely the extension of a literary work into another form, or as a separate work entirely. Cronenberg's Naked Lunch takes that decision out of the viewer's hands to the extent that it's not really an adaptation of William S. Burroughs's novel at all—at least if adaptation is conceived primarily in terms of story. While most of the movie's major characters and settings (as well as the famous "talking asshole" anecdote) come from the Burroughs novel, it also draws from other Burroughs writings as well as the author's life. Seeing Naked Lunch is in no way a substitute for reading the book, or vice versa—which may be precisely the point.

Talking centipedes and organic typewriters notwithstanding, Naked Lunch is relatively restrained by the standards of Cronenberg's previous work, marking, along with Dead Ringers (1988), a transition between the director's visceral early films and the cooler, more formalist late work. The outré visual effects are played more for laughs than chills. Indeed, Naked Lunch might be Cronenberg's funniest film, beginning with the ironic casting of Robocop himself, Peter Weller, as the alter ego of the outlaw writer. Weller's stone-faced performance positions the film's protagonist, William Lee, as a straight man (pun intended) who takes its bizarre happenings in stride. Recounting a not atypical incident in which his Clark Nova typewriter kills and disembowels a potential rival instrument, Lee deadpans: "I understood writing could be dangerous. I didn't realize the danger came from the machinery."

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment