by Michael Koresky

Reverse Shot

I opened my wallet for Jesus. And then, after paying the ten dollars and twenty-five cents, sitting through the ear-splitting, retina-scalding Regal Cinemas’ 2wenty (“Remember to arrive at the theater early!”), ads for Eclipse breath-freshener and Coca-Cola, bulbous oversized M&M men and a TNT “We Know Drama” sensory overload, I was ready to be saved. Lifted out of my seat, perhaps, and brought back down into my chair just in time for the beginning of lent.

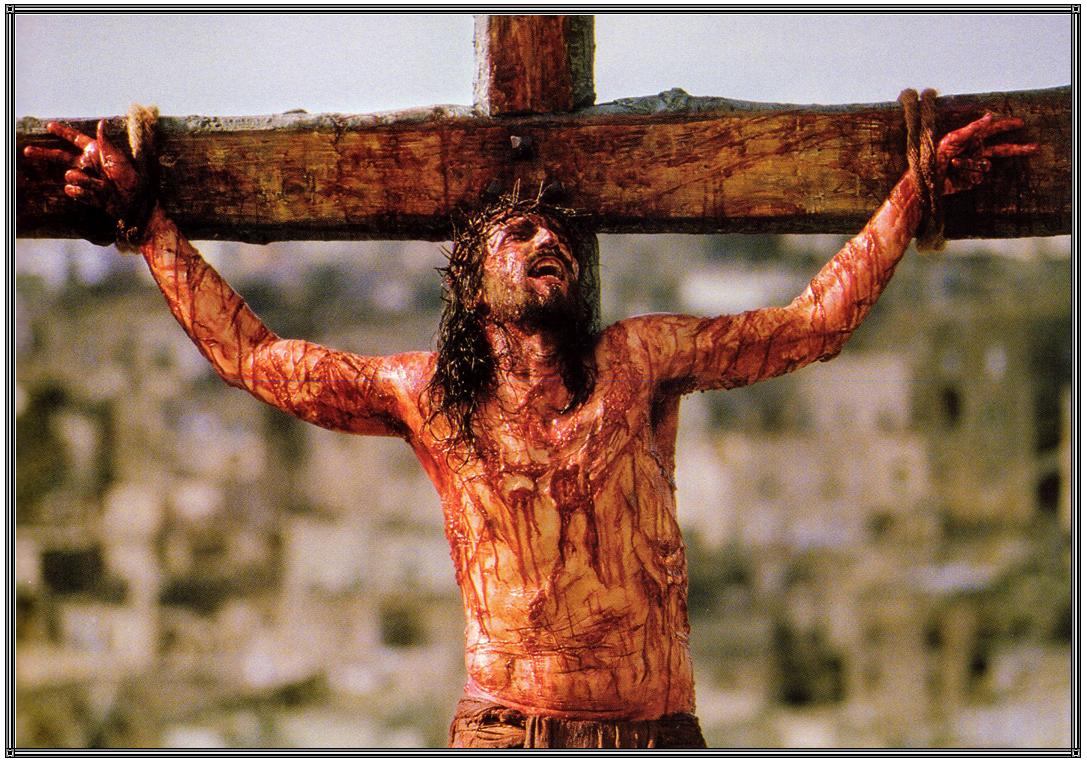

Alas, in the end, it was a movie. A mere movie. Mel Gibson’s brilliantly cynical marketing strategy, buoyed by the ADL’s advance work, lured even us non-believers (sinners) into the theater; certainly we didn’t expect to emerge as right-wing Christian fundamentalist converts, but we had every right to think we would be witnessing an honest representation of human and artistic faith, a spiritual roadmap to the psyche of a filmmaker and actor who felt driven, even instructed by God, as he has claimed, to create a cinematic likeness of the divine. It’s not essential that a moviegoer agrees with the political or religious implications of the images emblazoned on the screen, but that the images translate as a response from the filmmaker’s soul, that we believe we are witnessing the gospels as Mel himself sees them. The sheer divine force offered by Pasolini, Scorsese, by Bresson and Burnett and Spielberg, by Alexanders Payne and Sokurov, manifest in images that relinquish themselves to whatever artistic means necessary, not in shameless grandiosity that wishes to pummel the viewer into submission, into terrified acceptance. Gibson may find disingenuous the earthy benevolence of Pasolini’s Christ and the psychological torment of Scorsese’s, the lyrical allegory of Bresson’s Balthazar and Spielberg’s E.T., the spiritual personification of Payne’s Warren Schmidt or Sokurov’s cancer-ravaged saint-mother; he wants a more direct address, to make you feel every thrust of the rusty nail as it’s hammered into Jesus’s palms, to clutch your own shoulders as Jesus’s arm is ripped out of its socket, to cover your eyes in gratitude when the crucified thief’s eye is plucked out by a vengeful crow, to reverently ooh, aah, and shriek when Jesus is scourged, his back torn and ripped open into a hundred fleshy strips. Apparently to Gibson, there is no metaphor in religion; faith manifests itself as a spiritual dead-end, a believe-it-or-be-damned expression of finality. Of course Gibson, progeny of his fundamentalist missionary father’s terrifyingly stubborn outmoded beliefs, ended up a Hollywood actor—that particular “dream factory” churns out endless expressions of American complacency every year, cheerless damning spectacles of moral righteousness and unambigious carnal pleasures. Of course Mel Gibson, though a self-avowed man of endless spiritual vitality, can only depict the divine through the employment of hundreds of buckets of stage-blood. With its ludicrous, Hollywood-fortified conviction (not the same thing as faith, incidentally), Passion may be the world’s first completely banal Jesus Christ film. And though it’s remarkably, hopelessly literal, it was certainly waiting to happen. It had to happen.

If 2000’s Gladiator ushered in the new Bush regime, then perhaps Gibson’s blockbuster is the new 21st-century’s first true coercively conservative “classic.” Rarely has a film with a fundamentalist core been so blatantly conceived, so forthright in its admissions. Every decade of American film, though never preoccupied with anything grander than itself, nonetheless ends up a product of its own political backdrop. First Blood and its subsequent sequels became emblematic of the Reagan era, literally winning Vietnam back from the liberals, reasserting the swaggering machismo of the American hero that Seventies Hollywood attempted to all but decimate. And just as Stallone enacted Reagan’s cloudy-headed right-wing version of recent history, Gibson’s Christ—“compassionate” Conservative, deliverer of that old-tyme religion—emerges from the tomb at just the moment of the Bush administration’s attack on civil liberties, and the attack on the Civil Rights of American gays launched by Dubya himself with full-on, unabashed old-testament condemnation. Those who speak out against Gibson’s film are automatically stigmatized as leftist rabble-rousers and hapless atheists; to deny its physical impact or so-called technical grandeur is to supposedly denounce Gibson’s personal belief system. What’s more essential is to realize that when Gibson’s savvy propaganda piece, meant to inflict a tough-love Jesus on the nation’s wayward souls, floods into 4,000 screens, another dam between Church and State begins to crumble. The youngsters of the Clintonian Nineties, finding solace in the emergence of a truly multicultural pop mainstream, need to be reclaimed by the right, shorn of their piercings and tattoos, and brought back to Sunday school; who better to do that than Jesus himself, this time, like Rambo, stripped to the waist, chained and whipped, flesh torn and limbs broken, but never down for the count?

To Read the Rest of the Essay More: Jeff Reichert: Jesus Christ Superman

No comments:

Post a Comment